Demystifying getAcquire and setRelease in Java

In this blog post I want to take a close look at the subtle difference between using

- getAcquire with setRelease

- and using getVolatile with setVolatile, or equivalently, volatile reads and writes.

I will start with the basic concepts, using simple examples. Then I want to discuss a classical mutual exclusion algorithm, and explain why it relies on volatile semantics, and acquire-release is not enough. Hopefully this will clarify the difference between these two concepts for you. It certainly did so for me.

getAcquire and setRelease

Before going into details, I want to avoid a potential source of confusion from the start. The reason why you don’t typically see the usage of getAcquire and setRelease in Java code, is that they are implied when acquiring/releasing locks, volatile reads/writes and by most operations available on the various atomic classes. The examples below would therefore also work if a volatile flag, or atomic get and set was used.

Having said that, let’s check the documentation: According to the Javadocs,

getAcquire “returns the value of a variable, and ensures that subsequent loads and stores are not reordered before this access.”

setRelease “sets the value of a variable to the newValue, and ensures that prior loads and stores are not reordered after this access.”

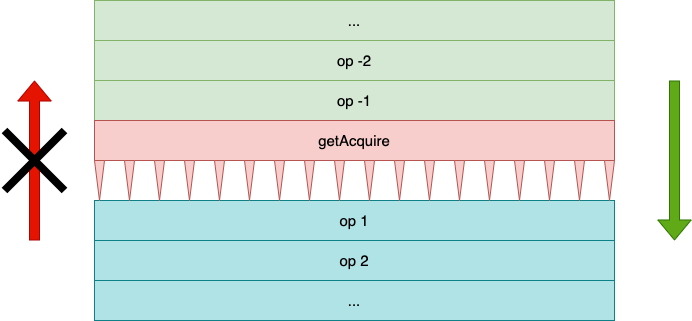

Thus, getAcquire acts like a one-way fence for all loads and stores that follow. I like to imagine it having thorns pointing

down that prevent operations from being reordered before it.

This diagram shows getAcquire with thorns pointing downward. Operations can be reordered after it, but not before.

This diagram shows getAcquire with thorns pointing downward. Operations can be reordered after it, but not before.

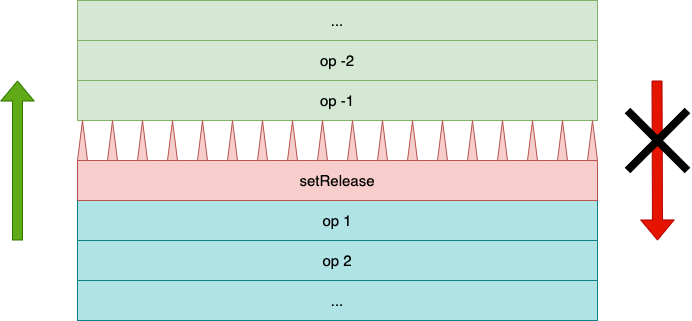

Likewise, setRelease acts as a one-way fence in the other direction as is illustrated below:

This diagram shows setRelease with thorns pointing upward. Operations can be reordered before it, but not after.

This diagram shows setRelease with thorns pointing upward. Operations can be reordered before it, but not after.

This means that getAcquire and setRelease, like volatile reads and writes, can be used to establish

happens-before-relationships across thread boundaries: If thread A, after an elaborate procedure finally uses setRelease

on a boolean done flag, all other threads that observe the flag to be true when reading it using getAcquire, can safely assume that A

is indeed done. Translated to Java, this means

AtomicBoolean done = new AtomicBoolean();

State state = null;

void threadA() {

state = initialze();

done.setRelease(true); // (1)

}

void threadB() {

if (done.getAcquire()) {

// Can safely assume that state is initialized because a

// happens-before-relationship has been established with (1)

assert state != null;

}

}

Note that the following code is broken and is just waiting to fail when you least expect it, since no happens-before-relationship is established by plain reads and writes:

boolean done;

State state = null;

void threadA() {

state = initialize();

done = true;

}

void threadB() {

if (done) {

// This assertion can fail, since the compiler

// or the hardware might have reordered instructions

assert state != null;

}

}

Due to the strong memory model of the X86 architecture (see Chapter 10.2 in Volume 3 in the Combined Volume Set of Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manuals) actually broken code like this has a high chance of working on X86 CPUs unless JIT interferes, but might start to fail randomly on ARM, which has a weakly-ordered memory architecture. This is not just a theoretical possibility, but can easily be demonstrated in tests.

Note that exactly the same applies to publishing objects with non-final fields:

class HasNonFinalField {

int nonFinalField;

HasNonFinalField() {

this.nonFinalField = initializeWithPositiveValue();

}

}

HasNonFinalField published;

void threadA() {

published = new HasNonFinalField();

}

void threadB() {

if (published != null) {

// This assertion can fail, since the compiler

// or the hardware might have reordered instructions.

assert published.nonFinalField > 0;

}

}

To fix this, we could transform it into

AtomicReference<HasNonFinalField> published = new AtomicReference<>();

void threadA() {

published.setRelease(new HasNonFinalField()); // (1)

}

void threadB() {

HasNonFinalField obj;

if ((obj = published.getAcquire()) != null) {

// Can't fail, since a happens-before-relationship has been established

// with (1)

assert obj.nonFinalField > 0;

}

}

Although often sufficient, relying only on the happens-before order established by getAcquire and setRelease can lead to

surprising results, as in the following example:

class ReleaseAcquireRace {

final AtomicBoolean started1 = new AtomicBoolean();

final AtomicBoolean started2 = new AtomicBoolean();

boolean first1;

boolean first2;

void run1() {

started1.setRelease(true);

if (!started2.getAcquire()) {

first1 = true;

}

}

void run2() {

started2.setRelease(true);

if (!started1.getAcquire()) {

first2 = true;

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

for (long tries = 1; tries < Long.MAX_VALUE; tries++) {

var race = new ReleaseAcquireRace();

var run1 = CompletableFuture.runAsync(race::run1);

var run2 = CompletableFuture.runAsync(race::run2);

run1.join();

run2.join();

if (race.first1 && race.first2) {

out.printf("Both threads won after %s tries%n", tries);

break;

}

if (tries % (1 << 20) == 0) {

out.printf("Never saw both threads winning after %s tries%n", tries);

}

}

}

}

Here, two potentially concurrently executing racers first announce that they have started, and then check if the other racer has already started. If not, they set a flag announcing that they were first, and exit. Studying the code carefully, it’s not too hard to see that these three outcomes are possible:

| first1 | first2 | explanation |

|---|---|---|

| false | false | both threads start at the same time |

| true | false | thread 1 wins |

| false | true | thread 2 wins |

However, if you execute the code from above, you’ll probably see a result like

Both threads won after 7021 tries

indicating that there is a fourth possibility

| first1 | first2 | explanation |

|---|---|---|

| true | true | both threads win |

How can that be the case? To understand what happened, remember that setRelease and getAcquire only act as one way fences,

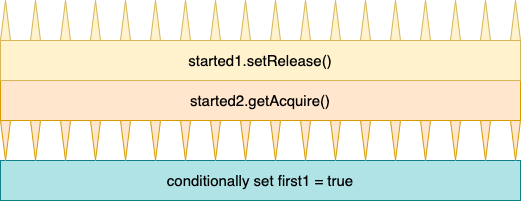

as illustrated with thorns in the diagram visualizing the implementation of run1 below:

This diagram shows the implementation of

This diagram shows the implementation of run1.

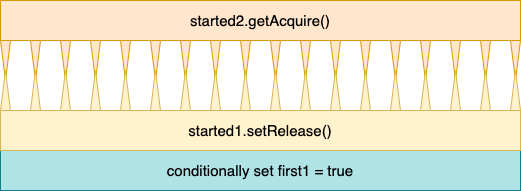

Therefore, the following reordering is legal, and explains the strange result, where both threads declare

themselves as winners:

This diagram shows a legal out-of-order execution of

This diagram shows a legal out-of-order execution of run1.

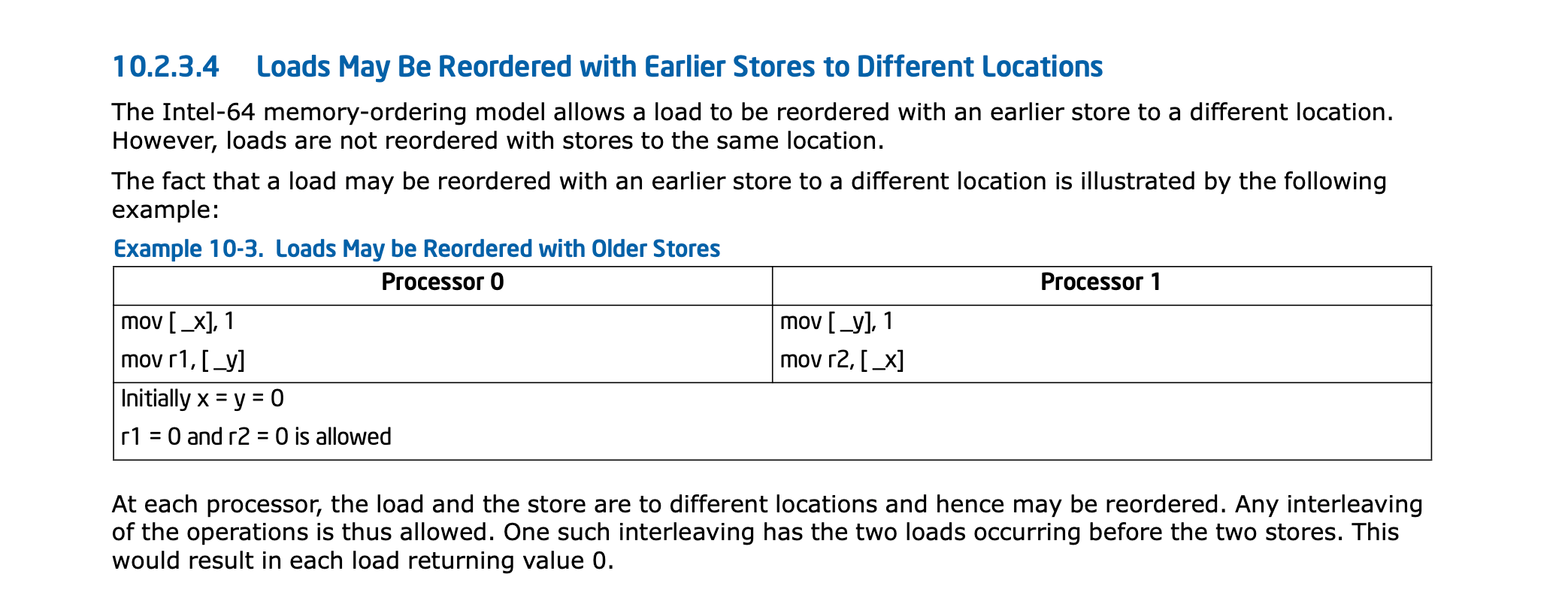

The discussed scenario is in fact explicitly mentioned in the Combined Volume Set of Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manuals:

The Intel SD manual, Volume 3, Chapter 10.2 Memory Ordering

The Intel SD manual, Volume 3, Chapter 10.2 Memory Ordering

You can verify that the above explanation is indeed the root cause of the unexpected result, by inserting

VarHandle.fullFence();

between setRelease and getAcquire in both run1 and run2 which prevents the problematic reordering.

Another way to exclude the possibility of both threads winning is to use volatile semantics, as implemented by AtomicBoolean.get and AtomicBoolean.set, which brings us to the next section.

Volatile reads and writes

As already mentioned, a volatile read implies a getAcquire and a volatile write a setRelease. In addition, every execution

of your program must be explainable by performing volatile reads and writes in a certain global order that is consistent with the

order of these operations in your program code. A more formal definition can be found in the

Java Language Specification. Note that this does not imply determinism or the absence of races between volatile operations.

It just excludes counter-intuitive executions that are not explainable without reorderings, like both threads winning

the race in the last example.

Let’s have a closer look as to how volatile semantics are relied on in a real algorithm.

The Peterson Algorithm

The Peterson algorithm is a classical concurrent algorithm for mutual exclusion. Unlike its modern counterparts, it does not rely

on atomic compare and swap operations implemented at the hardware level by modern machine architectures. It is therefore

significantly outperformed by even the most basic lock implementations that do, but of theoretical interest for the very same reason.

First and foremost, it’s a good example for a concurrent algorithm relying on volatile semantics that is less artificial than the

ReleaseAcquireRace from the last paragraph.

Although the Peterson Algorithm can be generalized to work with n threads, I want to focus on the two-thread version only.

To conveniently switch between different memory ordering modes, I’m using a small helper enum:

enum MemoryOrdering {

VOLATILE, ACQUIRE_RELEASE, PLAIN;

int get(AtomicInteger atomic) {

return switch (this) {

case PLAIN -> atomic.getPlain();

case ACQUIRE_RELEASE -> atomic.getAcquire();

case VOLATILE -> atomic.get();

};

}

void set(AtomicInteger atomic, int value) {

switch (this) {

case PLAIN -> atomic.setPlain(value);

case ACQUIRE_RELEASE -> atomic.setRelease(value);

case VOLATILE -> atomic.set(value);

}

}

// other operations....

}

The implementation of the Peterson Algorithm requires threads to have uniquely assigned indices, which must be either 0 or 1

and are accessed by calling ThreadIndex.current. After these technicalities, here

is an implementation of the Peterson Algorithm for mutual exclusion:

class PetersonLock {

private final MemoryOrdering memoryOrdering;

private final AtomicIntegerArray interested = new AtomicIntegerArray(2);

private final AtomicInteger turn = new AtomicInteger();

PetersonLock(MemoryOrdering memoryOrdering) {

this.memoryOrdering = memoryOrdering;

}

void lock() {

var myIdx = ThreadIndex.current();

var oIdx = 1 - myIdx;

memoryOrdering.set(interested, myIdx, 1); // (1)

memoryOrdering.set(turn, oIdx); // (2)

while (memoryOrdering.get(interested, oIdx) == 1

&& memoryOrdering.get(turn) != myIdx) { // (3)

Thread.onSpinWait();

}

}

void unlock() {

memoryOrdering.set(interested, ThreadIndex.current(), 0);

}

}

To enter the critical section, a thread first announces its interest at (1), and cedes the turn to the other thread at (2). Then it waits at (3) until either the other thread has no interest in the lock or cedes the turn to this thread.

Although succinct and elegant, this algorithm contains more nuance than meets the eye initially, and if you try

to reimplement it from the top of your head, you’ll probably discover that there are many ways to get it wrong.

Most notably, the tests I have written

fail unless MemoryOrdering.VOLATILE is used. To understand why, remember that with MemoryOrdering.ACQUIRE_RELEASE, a reordering

of the lines (1) and (2) is allowed. This, however, opens up the following possibility for both threads to enter the critical section:

| Time | Thread 0 | Thread 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | turn = 0 | |

| 1 | turn = 1 | |

| 2 | interested[0] = 1 | |

| 3 | observe interested[1] == 0 | |

| 4 | enter critical section | |

| 5 | in critical section | interested[1] = 1 |

| 6 | in critical section | observe interested[1] == 0 |

| 7 | in critical section | observe turn == 1 |

| 8 | in critical section | enter critical section |

| 9 | in critical section | in critical section |

To exclude this problematic reordering from happening, we can either use MemoryOrdering.VOLATILE, or insert

VarHandle.fullFence();

between (1) and (2).

Before coming to an end, let me say a few words about performance.

Performance Implications

I did some benchmarking,

comparing different variations of the Peterson Algorithm with each other on ARM and X86, with

inconclusive results. While the version with MemoryOrdering.ACQUIRE_RELEASE and an explicit fence is slightly

faster on my X86 laptop, MemoryOrdering.VOLATILE without VarHandle.fullFence() performed better on ARM for me. However,

I wouldn’t be surprised if you get exactly opposite results, since differences in execution speeds depend on the exact model

of your CPU and the specific JVM being used.

The only thing that can be said with certainty is that switching between MemoryOrdering.VOLATILE and

MemoryOrdering.ACQUIRE_RELEASE can have an impact on performance in either way.

Conclusion

getAcquire and setRelease can often be used instead of get and set with volatile semantics, but knowing where this is possible and where it might introduce subtle bugs requires a deep understanding of the implications and a careful, case by case analysis. My recommendation is therefore to avoid these methods except for the most performance critical parts or your application.