ScheduledExecutorService under Stress

In this blog post I want to closely look into the behaviour exhibited by ScheduledExecutorService implementations shipped with Java when faced with impossible demands. More specifically, I want to discuss what happens if

- ScheduledExecutorService.scheduleAtFixedRate is called with a runnable, that occasionally runs longer than the configured rate.

- scheduled and immediate tasks have to compete with each other for insufficient resources.

I want to conclude with some recommendations intended to address the aforementioned limitations.

What happens if scheduleAtFixedRate is not keeping up?

According to

the documentation,

ScheduledExecutorService.scheduleAtFixedRate

submits a periodic action that becomes enabled first after the given initial delay, and subsequently with the given period; that is, executions will commence after initialDelay, then initialDelay + period, then initialDelay + 2 * period, and so on.

But what if the submitted runnable takes longer to execute than period? This case is covered by the documentation as well, though it’s a bit vague about the exact behaviour:

If any execution of this task takes longer than its period, then subsequent executions may start late, but will not concurrently execute.

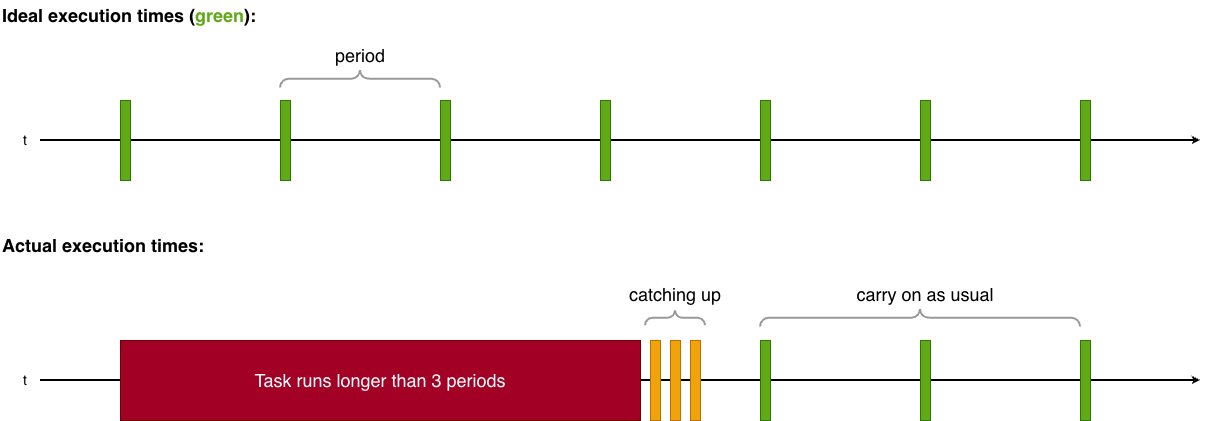

To figure out what the implementation actually does, I created a small experiment,

where the running time of a periodically submitted task exceeds the period of ScheduledExecutorService.scheduleAtFixedRate by

a bit more than a factor of 3 one time, and then falls back to runtimes way below period.

Here is what I got, visually summarized:

As you can see, the implementation compensates for the initial delay by scheduling one task right after the other until it has arrived at the expected execution count, and then proceeds as normal.

What happens if directly submitted and scheduled tasks get in each others way?

The Javadocs of ScheduledExecutorService state:

Commands submitted using the Executor.execute(Runnable) and ExecutorService submit methods are scheduled with a requested delay of zero.

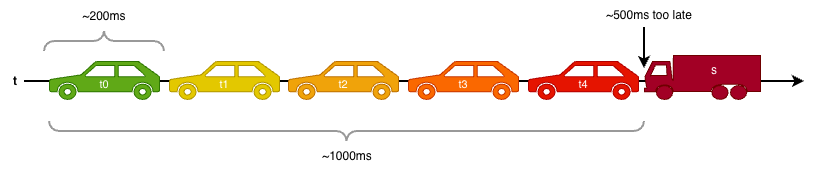

Note the implications: If you submit 5 tasks, t0, ..., t4, each running for 200ms, and then schedule another task s, to be

executed with a delay of 500ms, some compromises are needed, unless there are enough threads.

Here is a visual summary about what happens in the above scenario, for a pool with only a single thread, like ForkJoinPool(1) or

Executors.newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor():

As you can see and confirm for yourself by running

ScheduledExecutorServiceSubmitGettingInTheWay,

the task s that has been scheduled with a delay of 500ms is not run before t0, ..., t4 are finished, and therefore runs with

a delay of ~1000ms, instead of the scheduled 500ms.

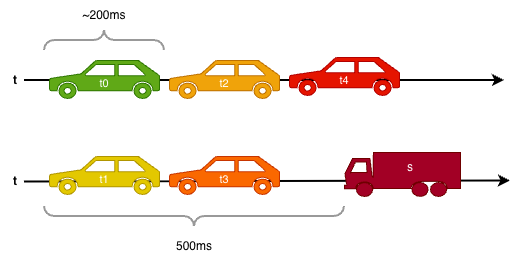

If we add another thread to our overloaded executor service, it looks like this, though the exact task to thread assignments will

of course vary:

Now t0, t1 and s are executed on time, while t2, t3 are delayed by roughly 200ms and t4 is delayed by ~400ms.

I hope that it is easy to see at this point, that at least 5 threads are needed in the above example to get rid of all delays.

Recommendations

ScheduledExecutorService implementations shipped with the JDK tend to be fairly reliable, but have to make trade-offs when faced

with impossible demands. Keep in mind, that other than the OS thread scheduler, the JVM cannot interrupt and resume threads at

will.

Let me conclude with some recommendations regarding ScheduledExecutorService:

- Create important schedules on dedicated executors, and monitor execution time as well as execution frequencies and/or delays, to detect problems early.

- If you have many periodic schedules, randomize initial delays to minimize the risk of schedules being executed in lockstep.

- Don’t use virtual threads to back

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutorimplementations, because apart from other reasons against it, doing so means implementing oneScheduledThreadPoolExecutoron top of another. See here in the JDK source code if you are interested in the details. - If you schedule lots of blocking tasks, consider decoupling the scheduling from the actual execution of these tasks, like in

scheduler.schedule(() -> worker.execute(this::blockingAction), 1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);where

workercould potentially employ virtual threads. However, note that without additional locking, this pattern might result in tasks from the same periodic schedule being executed in parallel.